![]()

|

UNBARRED

(UK)

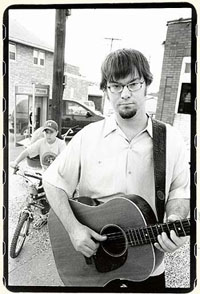

Although Jay Farrar (formerly Uncle Tupelo and previously Son Volt) has become a piece of Americana history, pinned with spawning a 90’s-on, alt-country movement and consequent media, he somehow easily transcends the genre. The past reveals that every monumental movement often begins and ends with its predecessor—Punk—-Sex Pistols, Grunge--Nirvana, Emo—-Sunny Day Real Estate—-and so on. Of course, this is all debatable and maybe even dispensable because, in the end, all music is subjective and not exactly engineered for category. It’s no coincidence that all the previous mentioned artists eventually despised their narrow placement. But the floating fact in all the alt-country muck is that Jay Farrar has always been chiefly concerned with being Jay Farrar—-coming with a perspective that evokes unique, real emotion despite the alt-country label. That’s the reason he can do things like self-release his own solo record and tour alone to packed houses. And, with what seems like two already rich careers behind him, there’s no hint of stagnancy. Terroir Blues, his second full-length solo release, is another move forward musically with even gutsier, more introspective lyrics. Backwards loops reminiscent of The Beatles’ Revolver are spliced between Farrar’s interesting take on ghostly folk. Songs like “Fool King’s Crown” mocks popular sentiment and culture with the help of lead Bottle Rocket Brian Henneman’s “electric slide sitar” while the ominous “Cahokian” explores a Mississippian civilization that’s erased Indian burial mounds through urban development leaving you to wonder if history is doomed to repeat itself. Loneliness of the moving American landscape and the realigning of feelings stirred from his father’s recent death, among others things, push his songwriting to an even more personal level. The album’s title is even a precursor to its tones of home—“terroir” is translated literally in French as “soil”-- a nod to the strong French influences in St. Louis, where Farrar currently resides. I caught up with him before a show on his current tour with Canyon in Nashville, TN shortly after Johnny Cash’s death. Notoriously tight-lipped in interviews, I was relieved to see he’s extremely friendly. It seems he prefers his music to speak where his quiet persona doesn’t. When he does talk, it’s deliberate and at his own pace. During conversation, he’s full of observations and intent on listening. Farrar met me for lunch in front of his ragged hotel-- a former Shoney's Inn turned Comfort Inn that he describes at best as “functional.” “It’s seen its better days,” he says. “I think the sign pretty much tells the story. They’re using the bottom part of the Shoney’s sign and they’ve got a tarp draped around it and it says Comfort Inn on top.” He immediately greets me by name and apologizes for a bag of oriental food in his hand claiming a friend persuaded him to get takeout. Nonetheless, it was such a nice day we decided to sit outside. So we maneuver across four lanes of traffic to a small sandwich place with a veritable desert of available, outside tables. “It looks like this place could use the business,” says Farrar. Never once did I foresee the day I’d be sneaking in outside food with the “alt-country bastion”—-but my day had come. As we sit down, Farrar orders a Diet Coke and politely ignores his food for the time being. Our waitress, Amy, clearly notices the bag but leaves without saying anything. (JF) We’re skirting the issue here. Yeah. She saw the food. (Upon her return, Amy rattles off the specials and Jay confronts the issue--) We have sort of a situation here…I have some takeout food and he’s probably going to order some food. Is that all right? Amy—

Thanks. (Although Amy turned out to be really cool, it was fairly obvious she’d never spent time differentiating between Son Volt’s Trace and Straightaways. Or, hey, who knows-- maybe she had. Nevertheless, I tipped her really well.) I appreciate you meeting me—it was really nice. Likewise. I guess when you’re touring, you have to do a lot of these…interviews. Yeah. It’s something that you have to get acclimated to-- talking about what you do as well as doing what you do. I would imagine. So, you’ve obviously played here quite a bit through the years. Do you like playing in Nashville? Yeah, it’s always been a good place to play. I played 12th and Porter last time and I’ve played the Bell Court Theatre before. But, I’ve probably been at them all. It’s kind of a memorable time to be here--Johnny Cash’s funeral was yesterday. Actually it was in Hendersonville where he lived—about 20-25 minutes from here. Yesterday? Really? Yeah, I went and saw Bill Monroe once in a little bar near there in one of those towns—Gallatin I think it was—is that a suburb? Yeah. It borders Hendersonville. I’m impressed you remembered that town. I’d actually read somewhere you have sort of a fixation with American small towns like that. Is that true? No…not really. I went to school in a small town. I grew up in a medium town. I’ve pretty much had my fill. They have something to offer in the short term but absolutely nothing to offer in the long run—-at least for what I’m doing. I’m no John Cougar (smiles). Did you listen to Johnny Cash? Oh Yeah. The riff from “I Walk the Line” was one of the first riffs I learned on the guitar. Other people may have been learning “Smoke on the Water,” but I was learning “I Walk the Line.” Of course, I knew “Smoke on the Water” too (laughs). There was a show in California and Uncle Tupelo got to open for Johnny Cash. We were only briefly introduced to Johnny but June was really sweet. She invited us out to her ranch and stuff. I think it must have been Johnny’s birthday or something. But we were on the road and couldn’t make it. Needless to say, we were bummed. (Amy returns to take my order and becomes enthusiastic over Farrar’s now sprawling food.) Amy—

(Jay just smiles and nods) So, your new record-- Terroir Blues. I’d read that you wanted to the go back to a more live sound rather than the more produced last album, Sebastopol. Yeah. Terroir Blues was kind of a dual approach. We were going for a live feel on most of the songs with vocals. And those are mixed in with the backwards-instrumental segments, which have nothing to do with live recording (laughs). I kind of like the idea of having that kind of contrast throughout the record. In general, I do favor live recording because it retains some more character essentially. Even if there are a few mistakes, you basically get better sounds that way. But I liked making Sebastopol too. It’s wherever inspiration takes you. If it’s having fun in the studio putting things together, then that’s the way to go. In most the reviews for the new album, I’ve noticed people commenting on your political stances, even though I thought Sebastopol had some sort of the same agendas—-songs like “Feel Free” and even “Barstow.” Has there been a change in attitude or just a newer, more outspoken avenue? I’m always kind of wary about writing about politics. There are always more people that are into it and know more about it. It’s more of a peripheral thing for me in regards to songwriting. But I want to be able to do it if I feel it. If I’m feeling it I’ll write about it. But, no, it’s something I generally try to keep subtle and not beat people over the head with. You just recently started your own label, Act/Resist Records. Have you found it positive so far? Yeah, It’s been mostly positive, it is a learning experience but I’ve been on the other side of the coin working with various labels enough to know that being involved with your own label is the way to go. It’s essentially to put out only your records right? Yeah. That’s the way it’s setup right now—-just to do stuff that I’m involved with. I guess I’m kind of keeping it open to putting out other releases but I’m not really setup for that right now. It must be pretty empowering. Do you think financially this was the better way to do it? I don’t know yet (laughs). Probably. My guess is it is. That’s not the reason I did it this way though. I mean, the primary reason is total control—-creative control. It’s a situation now where I can pretty much put out what I want, whenever I want. Record labels always have their own schedules and will often have their own ideas about the end product—-the end result--because they’re putting the money up for it. Well, it’s amazing that you’ve found your own niche and can do it this way—-with such a devoted following of people. This new tour features Canyon as your backing band. How’d that come about? Someone passed their CD on to me and I thought it was cool. They’re drawing from a variety of influences and making something new out of it. They weren’t easily categorized. I had a chance to see them play in D.C. and really liked them. Since they are a band already, they sort of have their own synergistic thing going on so I’m just kind of stepping in and enjoying it really. I play some solo stuff on this tour and some band stuff so we kind of alternate. You’ve had quite a bit of success overseas as well. From playing over there, do they respond the same? I’ve found it generally similar. I have a lower profile in general over there because I don’t tour as much and the records haven’t been released in some of the countries. Any memorable places you played overseas? London—been playing shows there and had records released there since Uncle Tupelo. It’s really not that much different. Other countries have been good too—-Germany, Spain. I like it--and I pick up a few new words every time (laughs). Yeah, I guess people are people everywhere—relate to the same hurts and joys. But with newer artists, sometimes it seems like actually conveying a message-- saying something—-is hard to come by. Do you sometimes get disenchanted with newer music? Yeah. It is easy to get pretty cynical about new music being thrown at you because so much is kind of generated by corporate record labels and spewed out. I do look at it positively. In the end, it’s all cyclical. Good music will come from the underground. When everything has reached the apex of being bad, things will be good again. Certainly The White Stripes are an anomaly. It’s great they are where they are. It’s nothing really I could have predicted. Do you think, with the music industry changes, it’s getting harder for artists to make a living at music or do you think these things are positive—bringing power back into the hands of musicians? I see Satellite Radio and the Internet eventually offering some new choices. You know, level the playing field. But, I don’t think it’s harder. It’s certainly gotten worse with the consolidation of radio. But for us [Uncle Tupelo], getting started out in St. Louis, there weren’t that many options either. We started out in this strip called The Loop near Washington University in St Louis. There were only a few clubs to play there. I think it’s generally better there now than when we got started. There’s a lot of clubs to play now. But in a way, it sort of simplified whatever goals we had—knowing that there was only one club to play—that was where we played. The Sony/Legacy anthology and reissues have created quite an Uncle Tupelo resurgence. Do you think it’s a misconception that, when it was actually happening, there was a monumental movement? You weren’t as championed or even as big at the time right? Not big at all—-we pretty much played small clubs across the country. There was no sense that it was really a movement. There was us, the Jayhawks, and that’s about it. So yeah, it’s kind of a misconception that there was this great movement. Even now touring since the Uncle Tupelo releases, I haven’t noticed a difference really. People do seem to want to hear some of the older songs a little more but that’s always been there for the most part. The main thing that I thought was good about it [the anthology] was some of the unreleased songs were put out. It kind of gives a broader perspective of what the band was all about-- to have some of that other unreleased studio and live stuff out there. I finally got around to watching The Last Waltz recently—-the Martin Scorsese film documenting The Band’s last show. Have you seen it? Oh, Yeah. In it, there’s a part where Robbie Robertson is talking about the road--how it’s no way to live and he can’t bare to think of more time spent there. It seems true albeit cliché. And you’ve obviously spent a great deal of time now on the road—how long now? Approximately 13—probably 15 years—give or take a year. What are your thoughts on touring? Well, I think it’s a necessary component of what it means to be someone creating music. If you’re just holed up in a studio the whole time I think you kind of lose touch with what it’s all about. I do have a family now and you kind of have to try a little harder to make it work but, in the same token, it’s basically what I do so my family has become acclimated to it. I bet being a father has been a huge growing experience for you…lots of challenges and revelations. Yeah, sometimes there are daily revelations, sometimes it’s a kind of cumulative effect of appreciating your existence—their existence. I guess you become a little more existential. I don’t know where this conversation is going (laughs). But yeah, generally more appreciative of things I guess. It's cool to see the kid’s acknowledgment and development—-even in regards to music. They are trying out new language. My son was kind like rapping and he’s three but he’s never heard hip-hop you know—it seems like an innate thing just working with language that way. Is he generally interested in music? I mean, I know he’s only three. Actually, he’s more into sports than music. (Farrar finishes his fortune cookie, reads his fortune, and puts it in his pocket) What did your fortune say? Oh yeah—it was pretty good. (He takes it out and reads aloud in a mocking voice.) ’Your road will be made smooth for you by good friends.’ (He smiles and puts it back in his pocket and wraps up some rice and the remainder of his food) Looks like I got dinner too. Well, I see your songwriting on a broad level, meaning the many people that have related to your music over the years. Obviously you see this on the road—-the people who have followed your career and will maybe even tell you how much they appreciate it. Do you see that as sort of the ultimate reward—-or more embarrassing? It’s both—it’s embarrassing and there’s an element of fulfillment in there. Someone has been affirmative about something that you’ve created. It helps you keep slogging it out. But I don’t necessarily think of it in terms of what people are going to take away from my music—what they’re going to get out of it. I think of it in terms of it’s maybe another option out there that they aren’t going to get in mainstream media. The definition of success for me is just to have a creative outlet—I think that’s the ultimate reward. And hopefully, people can find something in it. J.D. Rush is a writer for Goldmine Magazine in the States and kindly let unbarred publish this article. |